Off the Chain: American Art Unfettered

Amy Sherald

May 1, 2015 – May 30, 2015

Images courtesy of the artist, Erica Barnes, Rick Stillings, and Courtney Coker.

“If it’s true that culture is a set of social and political boundaries that are marked and contested in performance, then we might ask what happens to culture when the performances people give are determined, in part, by the interpretive framework of others.”

—Michael Bowman, Performing Southern History

Sherald’s large-scale canvases walk the fine line of separating notions of color from race by omitting “color” from portrayals of racialized, objectified bodies. Over two decades ago, her style of painting began as a series of fantastical narratives, or fairytales that, for her, illustrated subaltern ways of being in response to the grand narratives of stereotypical blackness that populate black history. She combines these elements into a social narrative that occupies what she calls, a “practiced position” or the roles that are played within the specific context of her work. Sherald states:

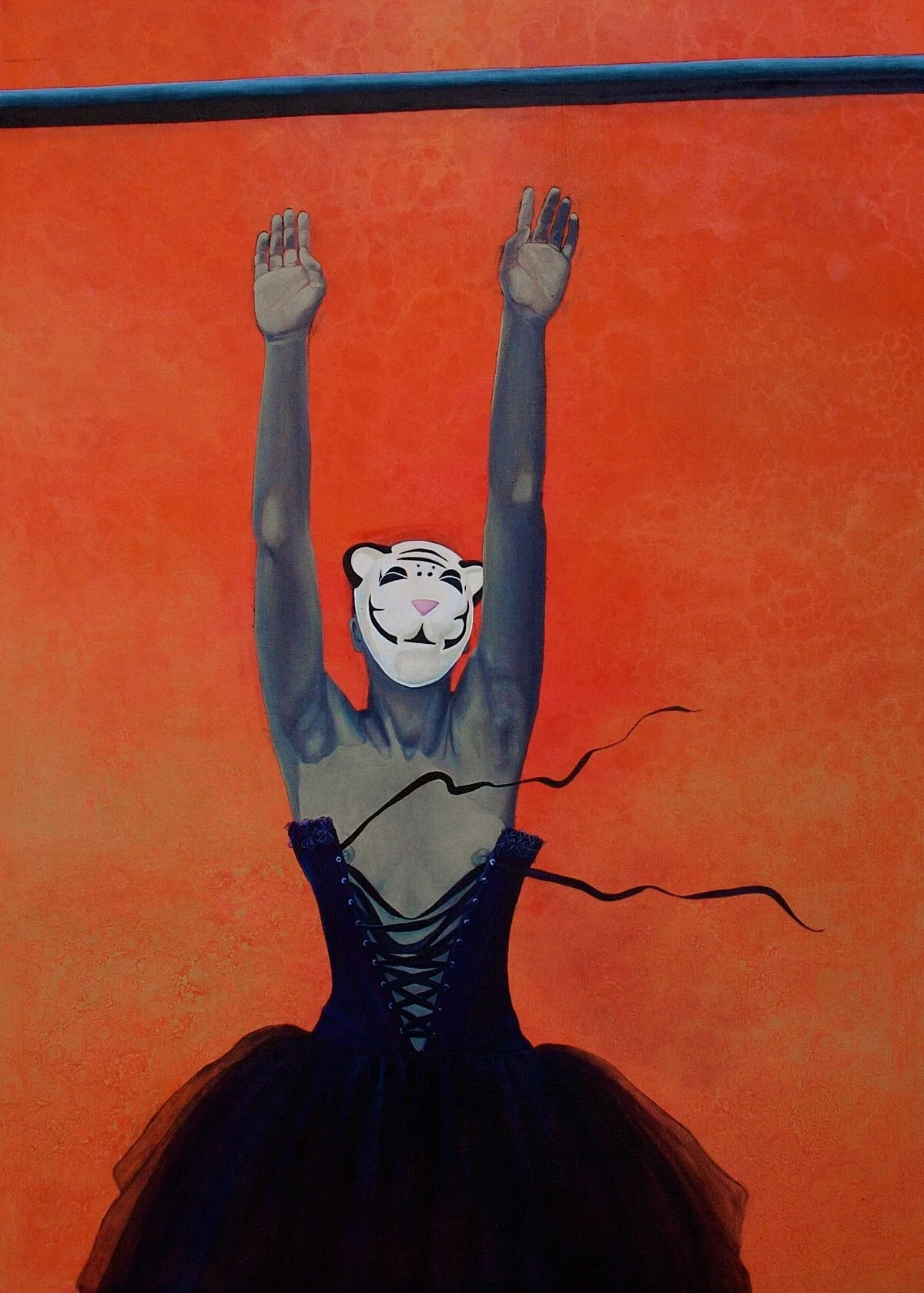

“As my ideas became more legible, the use of fantasy evolved into scenes of spectacle (e.g. circuses), to make direct reference to blackness and racialisation. I stage specific scenes of social ascent and racial descent that chart the psychology and performance of identity with a particular attention to notions of social exclusion and assimilation.”

By constructing space, narrative, and identity within her paintings, Sherald shapes porous borders between the performed elements of her characterizations and the ways that blackness is often defined in real life. She stages the performative aspects of her work as a way to address the myths and realities of perceptions of black life in American media and popular culture, and to examine the psychological effect of these stereotypical renderings on real people.

In her work, Sherald questions a sense of entitlement and marginalization that is embedded into social power structures that she upends in her work, and she manipulates disparate notions of race and the performance of blackness for real audiences – in movies, the media, and on stage – or for those who voyeuristically observe black life from a safe distance at the fridges – while imagining their gaze to be invisible, harmless, undetected, and okay. Sherald also considers historical race relations as a subject of present-day critique that seeks to find meaning and agency in places where the decks of power have heretofore been unfairly stacked. And while her intentions are neither meek nor incendiary, she uses provocation, satire, and an awkward self-consciousness as methods for creating a confrontational space that positions identity and rage, posturing and well-being, and the evolution of identity on the precarious edge of the frontal planes of her canvases as a means to direct attention into the direct engagement of the straightforward, emotionless, fixed gaze of her constructed subjects.

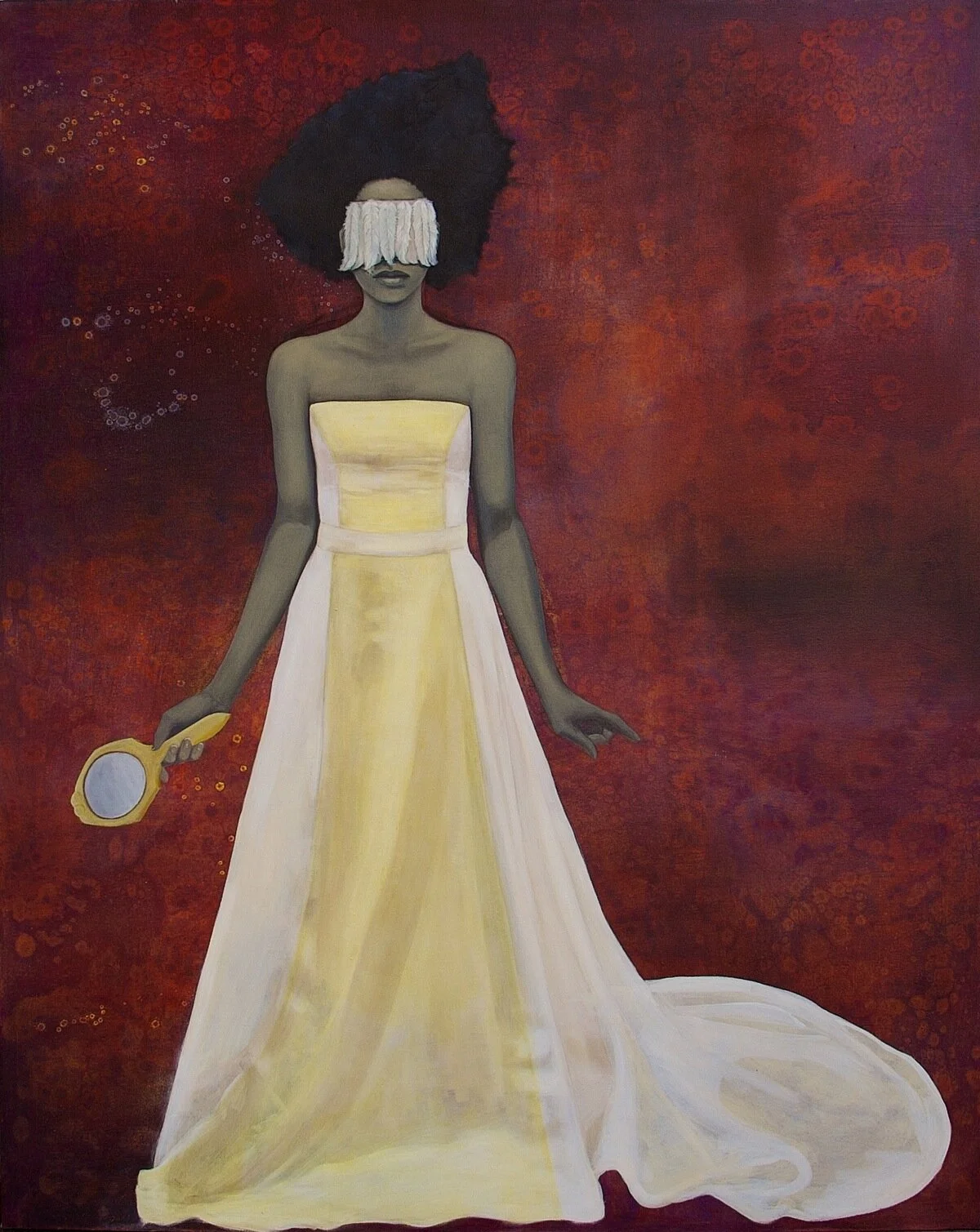

Sherald’s work is personal and universal; by looking inwardly she extrernalizes a world of possible meanings. Her subjects exist in a fictionalized purgatorial landscape, and a shiny veneer of nowhere space that draws one in, but not too deeply. Statuesque, well-dressed and profound, Sherald’s subjects are often mirror-selves around whom she creates both gravity and mystery. Her intricate process begins with attention to the details in her surroundings – a keen focus that is trained on what others miss. Her starting point is a chance encounter with someone who embodies a specific set of characteristics that resonate with her. Her search for models is continuous, and followed by choosing or creating their costumes. She then paints each figure in gray hues, and photographs the models in color. The skin-tones that she develops are translated into gray on canvas by using black pigment and Naples yellow. Next, she positions each character within a shallow, atmospheric landscape or a liminal space that does not convey a sense of context, place, or time. By building her surfaces, portraits, and scenarios in this manner, Sherald commands her audiences to engage with each painted figure in a face-to-face encounter that is rendered as if it is staged under a spotlight. She says of her work that, “The liminality of the background also represents the amorphous personal space of my own existence within the context of black identity and my search for ways to clarify and ground it.”

Through each unique character, set, and painting, Sherald finds and unfolds an aspect of herself. In finding and engaging with strangers with whom she connects, as an artist, she builds upon a found persona that represents – somewhere on a spectrum from casual to formal – a distinctive psychological self-portrait that stands in for aspects of idealized past, present, or future selves. While her work is situated solidly in the realm of contemporary art, Sherald evokes layers of complex tropes from historical American identity contructs that are deeply colonial.

From her Southern upbringing, Sherald incorporates formative memories in which she was one of less than a handful of black students in the private schools that she attended. Raised with the keen awareness that her demeanor, comportment, speech, and actions were all significant, her work now examines how this early episode affected her sense of self, and how aspects of the performance of identity cultivated then became engrained within her psyche, and appear in her paintings as ways to contend with notions of social acceptance, belonging, and assimilation. Sherald states, “[By] drawing from these experiences, I am engaging from a personal perspective with the desire to extrapolate meaning on how identity is both constructed and performed within political, social, economic and cultural spheres.”

As an artist, Sherald finds myriad means to shift her concern for identity from her roots as a Southerner into a global positioning device. She is thoughtful and intense in her technical and painterly evaluations of what color means on and below the surface – her surface. As she considers the broader implications of the ways that her being in the world shapes other interfaces – as an artist, as a woman, as a person of color – she finds layers of interconnectedness between the way she works and the way she is. These observations have shifted her process, of late, from one that began with a critique of performed blackness as a way to address a feeling of solo-ness in a sea of otherness. This had, for over decades, manifested in her work as representations of singular figures. Her new paintings now feature more pairings and groups. Sherald has also, for years, found inspiration in erasing the erasure of racism in her work through a particular focus on the rarified black subject, and now she includes a diversified range of individuals who bring new pluralities to her canvases. In this way, Sherald’s new mirrors reflect the negotiations, tensions, growth, and contradictions found in real life circumstances that call for us to respond to the proximity of difference.

EXHIBITION SPONSORS

Women For Art and The Community Endowment in the CACF

Anonymous (4) • Chloe Ball • Erica Barnes • Nancy Bass

Colleen Bassett • Kelli Block • Janis S. Chevalier • Courtney Coker

Karen Jaegerman Collins • Elizabeth Crawford • Scheline Crutchfield

Charlotte Dammann • Deirdre Davie • Catherine Dee • Julie Dixon

Lisa Draine • Therese Elron • Stacey Evans • Susan Fleischmann

Pamela Cole Friedman • Sylvia Gage • Linda Goodling in Memory of Janet King

Deanna Gould • Cathy Kramer • Holen Lewis • Dr. Anna Magee

Monica Markelz • Virginia Michel • Hollins Mills • Lynn Mills

Mary Murray • Annette Owens • Audrey Sipe Phillips • Elizabeth Piper

Barbara Shifflett • Jane-Ashley Skinner • Anne Slaughter • Jennifer Slaughter

Russell Willis Taylor • Claire Holman Thompson • Linda Wachtmeister

Jennis Warren • Lyn Bolen Warren • Marilyn Wright • Sarah Boyts Yoder

Megan Eagle Kingdon • Tosha Grantham • Cate West Zahl

Sara Lee Barnes • Judy Rasmussen • Caroline Nunley Satira